My first encounter with pottery as an art form, rather than something food was served in or eaten off of or drunk from, came when my mother took a course at her local women’s club. One of the pieces she made was a dark green bowl. It was shaped by piling a few smooth rocks into a mound and draping a thinly rolled circle of clay over the pile. She used a blue glaze on it, but something happened in the kiln and it turned out green. I was impressed not only by the sinuous curves of the piece and its rich green color but also by the fact that the result was a happy accident. The shape was determined by a random assortment of stones brought to the class by the instructor, and the interactions of temperature and the other items in the kiln changed the color of the glaze.

My next serious encounter with pottery came in the mid-1960s when I was a student in Taiwan. The Palace Museum had just opened, and among its exhibitions were items from the Qing emperors’ ceramics collection. The emperors had access to the output of the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, as well as the accumulated treasures of their predecessors. They had exacting standards—pieces that were even slightly misshapen or had mistakes in glazing and firing didn’t make it into their collection. But the visible evidence that human beings could produce perfectly shaped pots and then glaze and fire them without flaws impressed me deeply. The precision of a Song dynasty green celadon teabowl is breathtaking.

Five years later, nine months in Kyoto introduced me to Japanese pottery and its sometimes different aesthetic and approach to pottery. I was on a student budget and couldn’t afford to buy any pieces, but I could visit museums and showrooms, and what I saw there shaped what I have come to value in pottery. A vintage Oribe or Shino-ware teabowl has a bluntness and skilled clumsiness every bit as breathtaking as the perfection of that Song celadon.

Twenty years later I visited the warehouse of an importer of Chinese art goods in Redwood City on the San Francisco Peninsula. There on the shelves were hundreds of perfect Chinese porcelains. There might be two dozen identical shiny vases, all the same size and shape, each exhibiting a flawless Song dynasty celadon glaze. Or a row of blue-and-white bowls, again all the same size and shape, all with the same pictures on them. The sight was disturbing—even appalling. In the modern world of machine-shaped objects, carefully controlled chemistry, and electric kilns with uniform temperatures, perfection is reproducible—and suspect. (No doubt, some of the objects I saw that day ended up being sold as “genuine” Chinese antiques.)

That experience also deepened my appreciation of the wares of art potters. Many can throw perfectly shaped pots on the wheel, but they cannot produce exact copies of the same object over and over. Even when formed in molds, each piece will be unique—there will be at least slight variations in shape and decoration. This doesn’t reflect a lack of skill on the potter’s part. It is because they’re not machines.

Unpredictability plays an element in handmade pottery. The uniqueness of a piece results from the interaction of the potter’s skill, knowledge, and experience with the uncertainty of the movements of glazes down the side of a pot, the airflow in kilns, variations in temperature, the placement of items in the kiln, the interactions of minerals and chemicals in the clay and the glaze, the random deposits of ash, smoke, and fumes. Skilled potters use their training and knowledge to shape and decorate a pot and to place it appropriately or advantageously in the kiln to expose it or shield it from the flames, smoke, and heat, but they can only influence the way the piece might turn out--they can't control it completely.

What attracts me to a piece is the unexpected. The first encounter is visual. Something about a piece—the shape, the decoration, the way that shape and decoration interact—makes it stand out. A perfectly shaped pot is an incredible achievement, but shapes don’t have to be regular and uniform to be interesting. The potter may vary a design in small ways, and a pot becomes unique. I have some pieces that look like the potter was angry or drunk or inept or clumsy—but the result is inspired. Decoration may enhance a shape, accentuating it or differentiating sections of the piece. Or it may work against it, blurring a familiar shape and obscuring or distorting the outline. A vase that if glazed in a solid color-- perhaps cream or a pastel green--would be insipid becomes lively and energetic when the surface colors are the result of pit- or wood-firing. The surface of the pot may become a picture field, which may or may not work with the shape. Decoration can be formal or whimsical. It can be an elaborate, detailed, realistic picture or a splash of glaze thrown at the pot and allowed to run uncontrolled down the side, its flow determined by chance and gravity. I favor the latter—the random is more intriguing than the planned. I tend to avoid the pretty or the cute.

The second encounter is tactile. Some pieces fit comfortably in the hands; others don’t. Some are well-balanced; some aren’t. Some have heft and body and gravity; others are weightless and fragile. A pot can be surprisingly heavy or light. The surface may be rough, it may be smooth. Whatever a pot is, it needs to be held and to be touched to be fully appreciated.

The qualities I value are uniqueness, the unexpected, the surprising, the random, the human. Pottery has been around for millennia. It serves human purposes. It is made by humans for humans, for a practical use, for decoration, for both. It can be graceful and fluid, airy; it can be blunt and weighty, earthbound. It can be beautiful; it can be ugly. Even mistakes can make a pot interesting. What it shouldn’t be is boring and uninspired and repetitious. It should be a delight to look at again and again. It should be difficult to determine the best side to display.

What a good pot has is a conjunction of shape and decoration. Part of that is owing to the potter’s talent, but some of it is the result of random chance. There are factors a potter can influence; there are others beyond human planning—a random gust of wind blowing through the open stoke hole of a wood-fired kiln can send a plume of hot ash swirling through the kiln, pitting the sides of the pots facing the air flow with black spots. The clay may contain trace elements of some mineral, and a familiar glaze interacts chemically with it and becomes streaked with a different color. In the end, what I want is serendipity—the happy marriage of the planned and the accident.

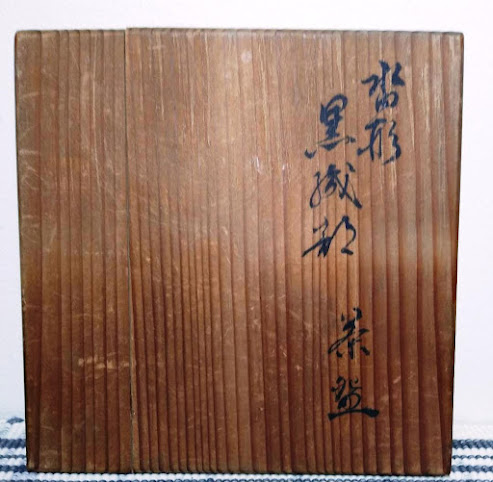

The Photographs and Other Conventions

I apologize for the quality of the photographs. Particularly with the smaller items, foreshortening comes into play, distorting their shapes. I find it difficult to hold my cell phone so that the items are level, and the tilts visible in many pictures in no way reflect the ability of the potter to create a symmetrical, upright pot. Unless the description notes that the body of a pot slants or is otherwise intentionally misshapen, blame me not the potter for any distortions.

To make up for the bad photographs, I give detailed descriptions of the shape and decoration of each item. The measurements are approximate. The more technical descriptions likely were supplied by the artist.

Generally the pictures are ordered as follows: a view from above showing both the mouth of the pot and the sides; side view(s); a view from directly overhead; a view of the base. If the decoration on the pot is uniform on all sides, I may show only one or two side views; if the decoration varies, I show all four sides. In the second case, the pots are rotated clockwise, and the sequence of pictures shows the succession of views as the pot is turned ninety degrees to the left.

Japanese and Chinese names are given surname first.

If the potter named the piece as a particular object, that is duplicated here. For example, if an American potter called a handleless teacup a yunomi, following Japanese usage, then the caption and description of the piece use that term, on the grounds that the name reveals something of the potter's intent and vision of the object.